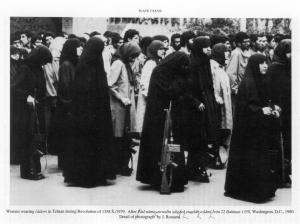

After watching Persepolis, I can’t decide if I wish I had watched it at the beginning of the semester, or if I’m glad that I waited until the end. Had I watched it at the beginning of the semester, it would have helped me with a lot of the novels that we have read. I didn’t know too much about the Iranian Revolution going into the semester, so I spent a good bit of time researching the topic. Persepolis does a nice job of giving a description of the events that took place in Iran. Yet, having watched it at the end of the semester, I was able to make a lot of connections with the novels that we have read. For instance, the scene in the movie where Marji is describing the end of the Revolution where prisoners were given the chance to swear their allegiance or be executed reminded me of a similar scene in The Bathhouse. Another scene that stood out was when Marji got caught holding hands with her boyfriend and her father had to pay a fine to bail her out. He says to her that when he was fifteen, he used to walk hand in hand with her mother, but the times have changed and that is no longer allowed. Mohsen and Zunaira also longed for the time when they could walk hand in hand down the street in The Swallows of Kabul. The scenes where Marji was sitting in the classroom under the strict supervision of the female teacher contrasted with the scenes of her walking down the street with her friends reminded me of the contrast between Kambili’s life under the watchful eye of her father and her time spent with Amaka and Aunt Ifeoma. Whether it be at the beginning or the end of the semester, I can definitely see the merit in watching this movie as part of a class on Post-Colonial Literature.

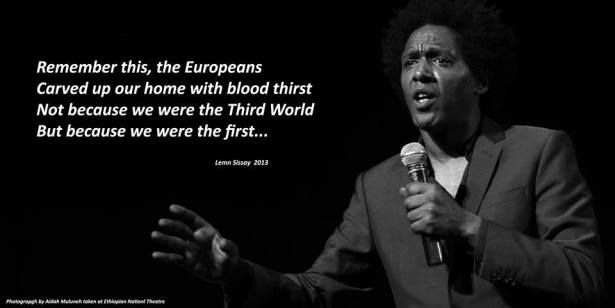

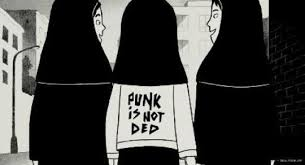

I didn’t really know what to expect when I sat down to watch the movie. I hadn’t read any reviews or even the synopsis of the film. I was a little surprised to see that it was an animated film. After having watched it, I found out that it was the autobiographical story of Marjane Satrapi and her time growing up in Iran. I think that using animation really was a brilliant move on her part. Had I been told I was going to watch a movie about a girl growing up in Iran during the Iranian Revolution, I probably would have zoned out halfway through. I think for many Americans, we just don’t know enough about Iran (perhaps care enough would be the more appropriate term) to get involved in a movie about a girl growing up in Iran. My curiosity got the best of me in the beginning, and it didn’t take long for me to get hooked. Stylistically, the black and white images add to the gloom surrounding Marji for much of the movie. It seems as though it only switches to color when she’s about to embark on a new beginning and she has a little bit of hope in her life. Of course, that never lasts long for Marji, and soon we’re right back to black and white.

Marji turns to her grandmother whenever she gets lost in the world. She always has advice to give, but it never comes off as preachy. This is probably due to grandma’s innate ability to throw in a penis joke whenever things are about to get too serious. She was definitely my favorite character. For as much as this was a movie about a girl growing up during the Iranian Revolution, it just as easily could have been about an American girl growing up in the city. The film does a great job showing the similarities between our cultures. Teenagers are teenagers all across the world. They all deal with angst and a sense of rebellion. They’re just looking for their place in the world. Persepolis does a great job showing that we are all a lot more similar than we are different.